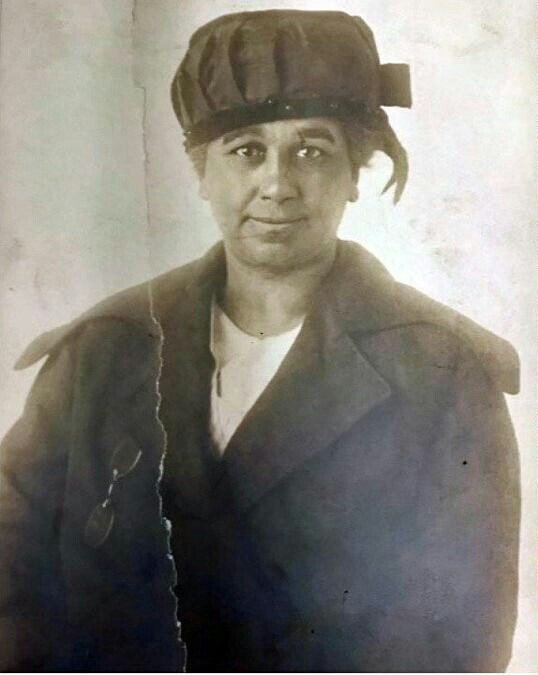

Bertha P. Whedbee (1876-1960)

First Louisville African American Woman Police Officer, Community and Political Activist

Bertha Par Simmons was born in West Virginia to Robert and Elizabeth Simmons. According to the 1880 census, her father was a laborer and could read and write; her mother could not. The Simmons had two daughters and an adopted son. By at least the 1890’s, Bertha had moved to Louisville and married Ellis D. Whedbee, a physician, in 1898. Her mother, Lizzie Simmons, signed the marriage certificate suggesting Bertha’s father had died because a father would have typically signed.

Born in 1863, Ellis Whedbee came from an enslaved background. His parents were farmers in North Carolina, and according to census reports, were illiterate. Ellis’s brother became an attorney and remained in North Carolina. Ellis graduated from Fisk University with a medical degree. He was one of the founders of Louisville’s Red Cross Hospital.

Many leaders in the African American community advocated having African American children taught by African American teachers. Whedbee likely would have had the same concern. Georgia Nugent and other leaders initiated the effort to train African American teachers. In 1901, Bertha Whedbee became one of five graduates from the first training class of the Colored Kindergarten Association, an auxiliary to the Louisville Free Kindergarten Association.

Bertha Wheedle became active in many local causes:

During WWI, led girls at the Phillis Wheatley School Patriotic League in growing food and sewing warm comforts for soldiers

Served on the Phillis Wheatley YWCA Board

Longtime contributor to the Urban League

Served on nominating committee

Honored in 1959 for twenty-five-years-service

Bertha was an original member of the Red Cross Association, an effort to provide healthcare to African Americans by African Americans. The Red Cross Hospital (not associated with the American Red Cross) allowed African Americans to be treated by African American doctors and nurses. Bertha made many contributions to the hospital:

Helped to train nurses

Chair of the Women’s Board of Managers after the death of its original chair.

Chair of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Red Cross Hospital

Officer in the Ladies Medical Aid

President of the Bluegrass State Medical Society

Served on the program committee of the National Medical and Dental Association

Bertha Whedbee was no shrinking violet. In 1919, her 17-year-old son, Ellis, was arrested by police after being stopped on suspicion of robbery As Ellis, Jr. was a respected model student, this stop was likely unwarranted. He was charged with disorderly conduct for trying to strike a police officer and was fined $10. Bertha Whedbee entered the police station and, according to a newspaper report, threatened to kill the station master. She was given a $10 suspended fine. Two days later, she and her husband filed suit against the station master. Three years later, Bertha Whedbee became Louisville’s first African American policewoman. She was hired “for providing a protective worker for the colored women and girls” but to work “strictly among girls and women of her own race.” One letter of recommendation from Mrs. J. B. Speed demonstrates Whedbee’s status in the community as well as the cooperative work among some black and white women. Mrs. Speed wrote,

I take pleasure in recommending Mrs. Bertha Whedbee for any position requiring faithful work, honesty, and industry.

My acquaintance with her is of about fifteen years, and I have never known her to fail in any duty assigned her.

In 1922 Bertha Whedbee testified in the trial of a white man accused of raping a five-year-old black child. Indicating the amount of evidence against him, the man was kept in jail for three weeks. Whedbee and others, including the examining physician and eye witnesses who saw the man leaving the girl’s bedroom, testified against the suspect. Still, the grand jury released the suspect. The Leader, a local paper, suggested the results would have been much different had the child been white.

In July 1927, Bertha resigned from the police department in protest. She may have been expecting to be dismissed whenthe only two male African American officers in the department were dismissed following a Democratic takeover of the city’s elective offices. The African Americans had been hired under Republican administrations.

In 1938, when the Louisville Police Department dismissed four policewomen in favor of hiring patrolmen, the Woman’s Auxiliary to the Taxpayer’s League held a session at the Seelbach Hotel questioning why Louisville should have policewomen. Former police officer Bertha Whedbee and the four dismissed policewomen (two black, two white) spoke to the February 25th meeting, after which The Taxpayer’s League recommended rehiring the policewomen. However the chief resisted and refused to rehire them.

The Whedbees had four children. Three of whom survived to adulthood. Roberta became employed at the Phillis Wheatley YWCA and became active in many of the organizations her mother had promoted. She died at a relatively young age, preceding her parents in death. Their sons, Ellis and Melville, were well-known in Louisville, partly due to their participation in sports. Mel was a star high school quarterback at Central High School. He later taught and coached at the Y. M.C.A. and Kentucky State University. Ellis was widely admired for the winning track team he coached at Male High School.

Bertha Whedbee is buried in Louisville Cemetery, alongside her husband Ellis. In 2018, the Jefferson County Police Department honored her with a gravestone. Her grave had been unmarked.

Sources

Bertha Whedbee personnel file, Louisville Police Department, Jefferson County Archives.

Indianapolis Ledger: 13 April 1918.

Louisville Courier Journal: 19 June 1901; 10 May 1919; 21 May 1919; 25 February 1938; 8 February 1942; 24 April 1959.

Louisville Leader: 10 November 1917; 27 August 1921; 3 December 1921; 21 January 1922; 4 February 1922; 25 March 1922; 13 May 1922; 20 June 1922; 29 July 1922; 28 October 1922; 25 November 1922; 2 December 1922; 26 My 1923; 15 September 1923; 6 October 1923; 28 July 1924; 23 July 1927; 1 December 1928; 24 May 1930; 5 September 1931; 16 September 1933; 18 November 1933; 10 March 1934; 13 October 1934;16 February 1935; 13 May 1939; 3 January 1942; 10 August 1946.

U. S. Census: 1870-1880. 1900-1940.